In March we took on International Women’s day with a pair of critical glasses. A now long corporatized affair, we decided to take the day head on and examine its radical protest roots and its relationship to today’s towns and cities. We were joined by Deborah Nagan, Selasi Setufe and Mary Holmes who made up our wonderful panel of women at different stages of their built environment careers to share their insights on what we still need to fight for.

A google search for International Women’s day, presents you with a collage of pastel pinks and purples representing women’s universal suffrage. On the ‘official’ International Women’s Day website, the mission statements from the glossy CEOs, the ‘glass ceiling breakers’, alongside the efforts of global corporations’ to honour the day are highlighted. Apparently even Google changes its Google Doodle on its search pages to honour women’s day. But, the actual radical history of women’s day has largely been forgotten. In 1908, 15,000 female garment workers marched through New York City demanding shorter hours, better pay and voting rights. A year later the socialist party of America declared a ‘National Women’s Day.’ A year after that at The International Conference for Working Women in Copenhagen, Luise Zietz and Clara Zetkin proposed that every country should agree on a day to coordinate global demands for liberation.

A google search for ‘International Woman’s day’ Vs one of the original posters by Karl Maria Stadler for the 1914 march which was banned by the German Empire.

On March 8th 1917 Women in Russia began a strike for “Bread and Peace.” Opposed by political leaders, the women continued to strike until four days later the Czar was forced to abdicate and the provisional Government granted women the right to vote. In its early years, women’s day was a day for ordinary working women, made up of strikes and marches that demanded social and political equality.

A recent visit to the exhibition, Women in Revolt at Tate Britain, a showcase of British art and activism during the women’s liberation movement of the 70s and 80s, displays photographs, prints and paintings filled with a similar radical spirit, including photographs of Jayaben Desai, born in India in 1933 and migrating to London in 1967. Jayaben led a predominantly female and South Asian workforce on a 2 year long strike to protest their treatment at the Grunwick film processing factory in North West London; proving that a woman’s place really is on her picket line.

Photographs from the Tate Britain Exhibition ‘Women In Revolt,’ of Jayaben Desai who led a strike against the Grunwick film processing centre.

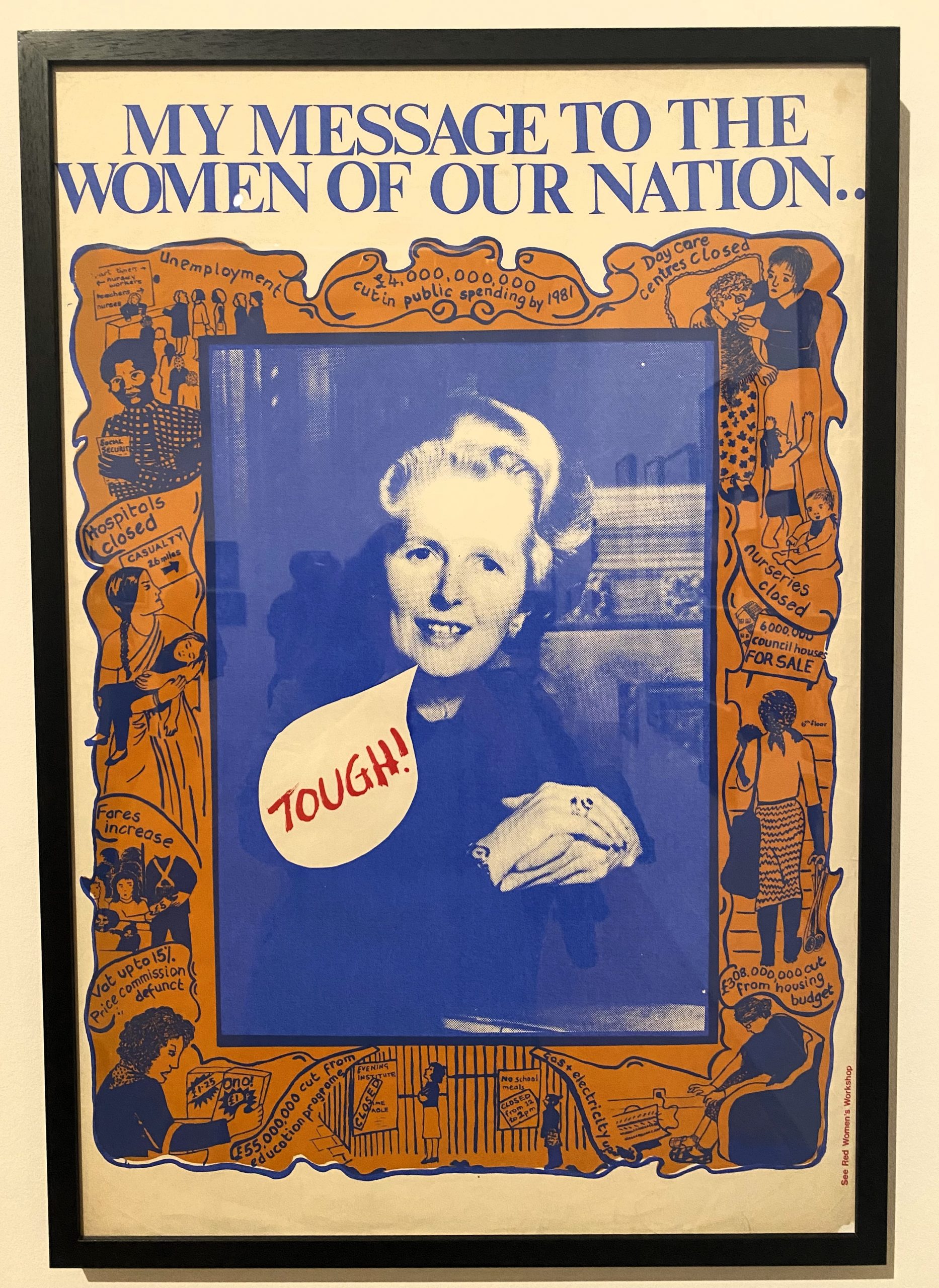

A print by The See Red Women’s Workshop, a screen-printing studio set up to contribute towards a new visual culture for women’s movements. Around the portrait of Margaret Thatcher are illustrations, detailing the impact government policies have on women and other oppressed and vulnerable groups, particularly around cuts to public spending. An acknowledgement that even women who have assumed power can still very much exercise harm against other women. A truly inclusive vision of feminism works actively in the interests of all women and where womanhood makes its intersections with other components of identity, meaning Women’s day should not be untied from economic, racial, social and climate justice.

‘Tough!’ by See Red Women’s Workshop, 1979

In our towns and cities, women make space for themselves whether they are asked how they’d like to live or not. These photographs by Jill Posener, ‘a dirty girls guide to London’ are protesting the time of section 28, where the public visibility of same sex affection was deemed a political act. But also saying that the city belongs to everyone including all marginalised sexualities and genders. Female dominated spaces very much make up our towns and cities, from women led housing and support centres, abortion clinics, places of sex work to the public square.

‘A Dirty Girls Guide to London,’ Jill Posener, 1987

We’ve recently been reminded that cities, and towns, our public places are constantly contested spaces. Thousands of us have taken to the streets in support of Palestinian liberation and a ceasefire, marching together in direct action groups, trade unions or as ordinary women and children. In the cities and towns of Iran just last year and before, women and girls protested under the slogan Jin, Jiyan, Azadî, – ‘Women, life, freedom’ in response to the death of Jina Mahsa Amini, a 22 year old Kurdish woman, who died in police custody for alleged non compliance with compulsory veiling laws.

Direct Action Group Sisters Uncut attend pro-ceasefire demonstrations in London. (23.12.23)

Or through occupying and reclaiming space, like on Claremont road in Leytonstone in the 90s, as part of the anti-roads movement. Houses and streets were occupied with nets, and streets were turned into sitting rooms, to protest demolition and the further building of motorways, expressing an alternative way to inhabit the city. And also to express a counter-cultural identity in British urban environments.

Photographs of the Claremont Road occupation in 1994 by Gideon Mendel

In 2017, direct action group Sisters uncut reclaimed and occupied the closed visitors centre of Holloway Prison, once Europe’s largest female prison. Alongside other grassroots organisations and local residents, the reclamation signalled the liberation of space from a violent history to serve as a resource for the community. After a 10 hour stand off with the police, the group were able to facilitate a week long festival that offered relational experiences such as collective meals, craft workshops and public education. The groups demanded that the land should be used to provide specialised, material support for survivors of domestic violence and provide social housing for those harmed by the criminal justice system, rather than selling the land to private developers and further investment in building prisons.

Sisters Uncut occupy Holloway Prison, 2017.

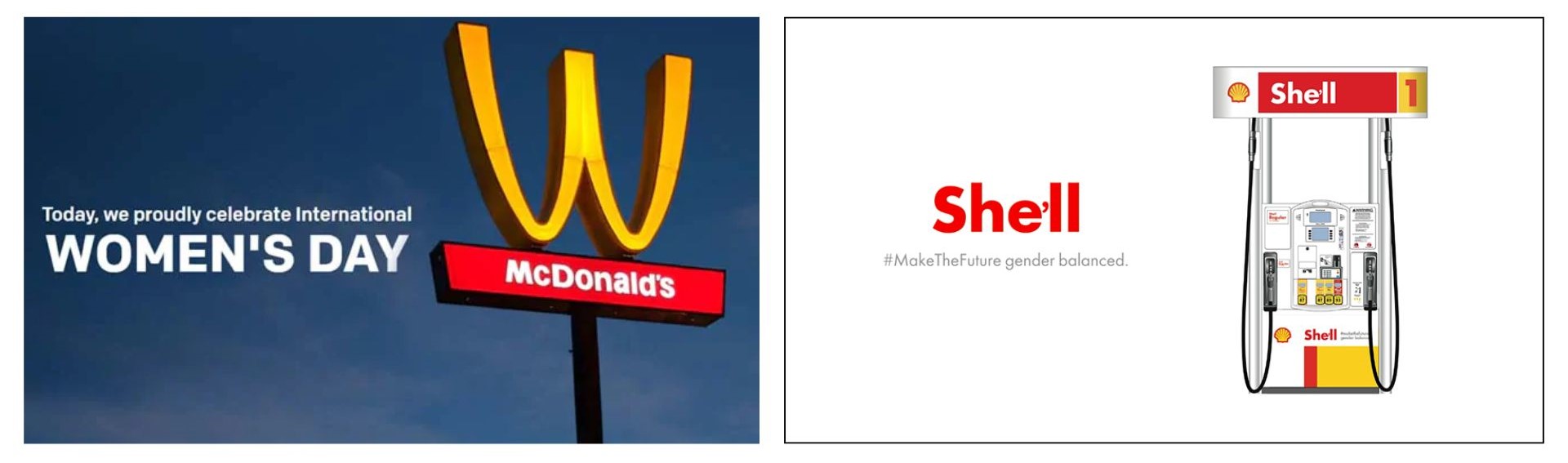

Is it possible in our modern world where oil company Shell turns their name to She’ll, or McDonalds flip their golden arches to create a ‘W’ for women’s day, attempts to honour actually revolutionary socialist histories do little but virtue signal and hide exploitative practices; practices which almost always disproportionately affect women and sell our oppression back to us as ‘empowerment.’ We should probably ask how often we are asking politely rather than demanding and how often we are strolling rather than marching. And where the place for protest lies in our future towns and cities. Especially in a time where such a right is being curtailed and the physical and public spaces where we organised are being tightly controlled. But for now we can celebrate women’s day by honouring its radical history, there is still much to defend and fight for.

Making Space for Women is a networking group for women in the built environment. We are open to all women in the sector, but our origins are in Waterloo where we were co-founded by WeAreWaterloo BID and Build Studios with Build Workspace. We aim to provide an informal opportunity for networking, and a forum for fascinating debate in a part of London known for its activism and engagement.